At the The Big Anxiety forum

Oct 6 & 7

RMIT Storey Hall & Green Brain

Building 16, 336/348 Swanston Street

Melbourne

9am – 5pm

Book HERE

Slice/silence – a project by Indigo Daya

In this commissioned project, Indigo Daya explores self-injury and silencing, and the implications of this in the larger context of societal silencing and blame around trauma and abuse. The project will be manifested through The Big Anxiety Forum (6-7 October) and in a series of artworks, discussions and web-based events unfolding during the festival.

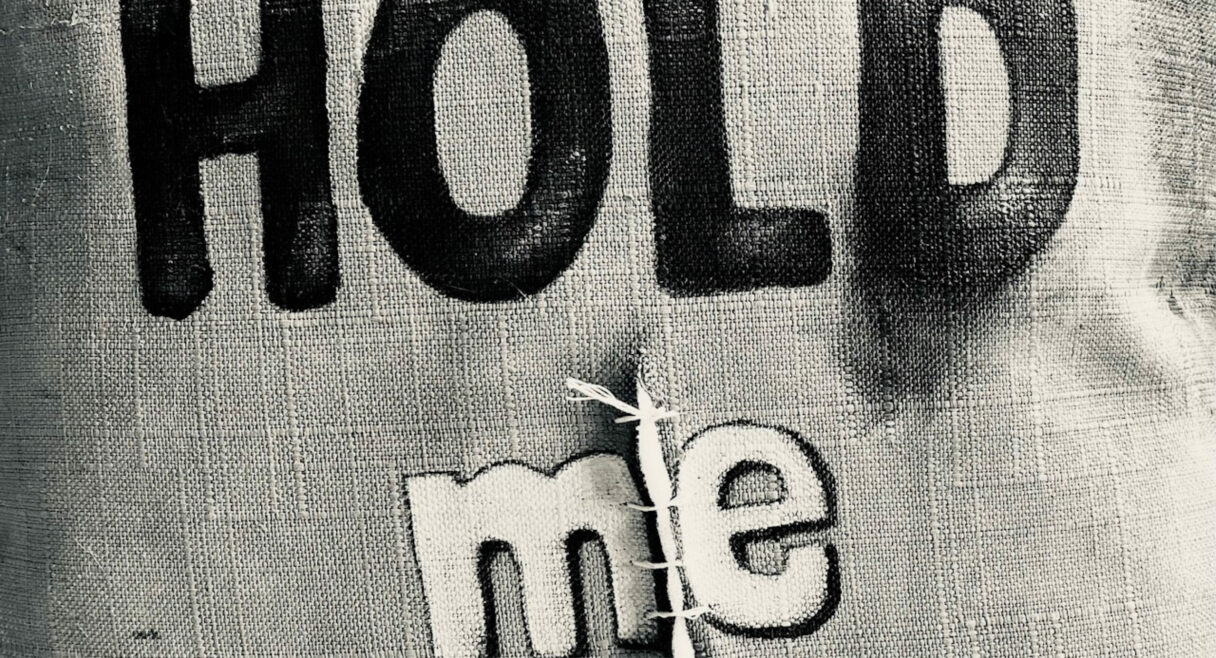

An installation at The Big Anxiety Forum will provide a space to cut through silence and explore self-injury openly. Cushions and pillows stand in for bodies, each one bringing a unique history of violence. Visitors will be invited to engage with the cushions and pillows in any way they choose: injure them, heal or tend to them, hold them, speak to them, read them, write on them, destroy them or love them. People can also contribute and interact with the space from an online portal or share them on social media using the hashtag #slicesilence.

Conversation circles will be held during the forum, facilitated by Indigo. Guests will be invited to openly explore experiences of self-injury, silence and injustice while interacting with the installation. The conversations aim to give voice to experiences around self-injury that are normally silenced rather than being welcomed or heard.

Note: Conversation circles will hold a similar philosophy to Alternatives to Suicide groups, in that there will be an absolute commitment to non-coercion, avoidance of pathologising, freedom to talk about anything and a recognition that self-injury is often rooted in experiences of systemic oppression.

More about self-injury

Control, judgement and criminalisation: Psychiatry and psychology have controlled the narratives about self-injury for many years, describing it as either a symptom of illness (inherently devoid of meaning) or as a sign of deviant, attention-seeking, manipulative people who are best ignored.

The medical system typically responds to people who self-injure in one of three ways: forcing us into carceral psychiatric institutions for forced drugs and shock treatments, dismissing us so we are alone in our crisis and pain, or sending us into therapy programs that teach us ‘socially acceptable’ ways to express our pain. In the UK, a recently disbanded program called ‘SIM’ (Serenity Integrated Mentoring) actually criminalised survivors.

In services we are required to cover up our scars and injuries and discouraged from speaking about them because it may be ‘triggering’ to others.

Silence, shame and erasure: Many survivors have stories to tell about what it’s like to be in the world with injuries and scars. We know the silent looks of disgust from strangers, or uninvited derisive comments. Some people think we are dangerous and they stay away. Some people think we’re in danger and they seek to report us.

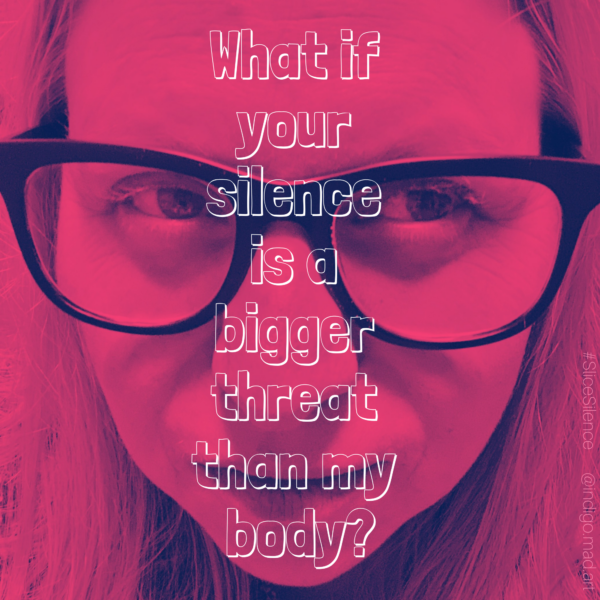

In social media worlds, we are reported, blocked, suspended, banned. If you search for ‘self harm’ or ‘self injury’ on Instagram, you will get a message about posts being hidden because they are dangerous. If we share photos of our bodies with scars, even if they are old and healed, filters will protect you from seeing us. We are discouraged from speaking or existing in any visible way. We are erased.

Trauma, power, voice and survival: Yet those of us who self-injure have different, richer stories to tell. For a great many people, self-injury is a survival strategy used by victims and survivors of profound trauma, including (but not limited to) child abuse, sexual violence, family violence, torture and incarceration. Self-injury can be seen as a meaningful, resourceful response to trauma in the context of having almost no other form of personal power. Our bodies, as sites of so much violence, can become the only place to express those things which have no words, which feel unspeakable and unhearable, to retain some sense of control in an unsafe world. Self-injury can be a way to transform emotional anguish which otherwise feels unbearable. Sometimes, self-injury can be the only thing that stands between us and suicide.

What does it mean when self-injury is silenced and hidden in a similar way to sexual violence and abuse?

What does it mean when we tell girls and women that their bodies tempt men to rape—and then tell survivors that their bodies are ‘triggering’ for others to see?

Could it be that our bodies are not triggers at all, but the place where the bullets hit?

Could it be that ‘covering up’ our bodies covers up injustice?

Could it be that we can’t have real healing or justice until we can speak and show our truth? Matt Ball, Director of the Humane Clinic and ‘Suicide Narrative’s pioneer, says that people living with suicide hold wisdom about injustice that the world needs to hear. Perhaps self-injury is similar, perhaps our scars hold stories that the world needs to listen to.

Image: Indigo Daya

Indigo Daya

Indigo Daya is a mad survivor activist, artist and academic based in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. She has worked inside and outside the mental health system for over 17 years, and is passionate about growing anti-oppressive, non-pathologising support that privileges the views of consumers and survivors. Her blog shares stories of hope, hurt and healing: www.indigodaya.com. Twitter: @indigodaya